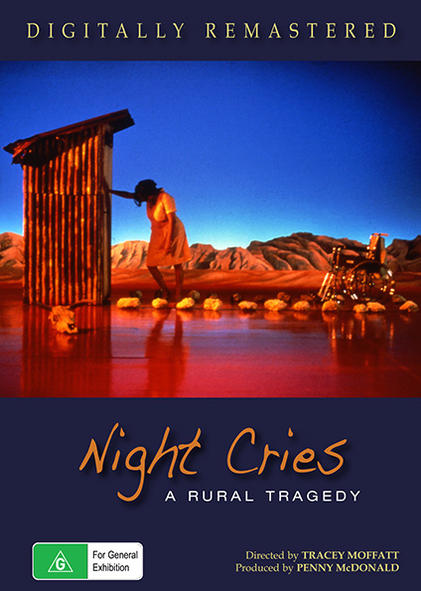

Night Cries – A Rural Tragedy

Producer: Penelope McDonald

Director: Tracey Moffatt

Genre: Short Drama

Run time: 17 mins

Year: 1990

Distributor: Ronin Films , Women Make Movies (wmm)

Links:

Buy:

For use by educational institutions or for public screenings:

In Night Cries a middle-aged Aboriginal woman and her invalid white mother are suspended in a soundscape. ‘A Rural Tragedy’, says the subtitle…’ A horror film’, says the subtext.

In basic narrative terms, NIGHT CRIES is a response to Charles Chauvel’s JEDDA (1955), about the fate of an Aboriginal baby adopted by a white mother in a remote outback station. In NIGHT CRIES, we leap forward to the white mother’s last hours, cared for, fed and washed, by the Aboriginal woman she had adopted and raised as her own. It is a profoundly tragic story, expressing the isolation of the Aboriginal carer, her separation from anyone else’s world, neither able to live fully as white or black.

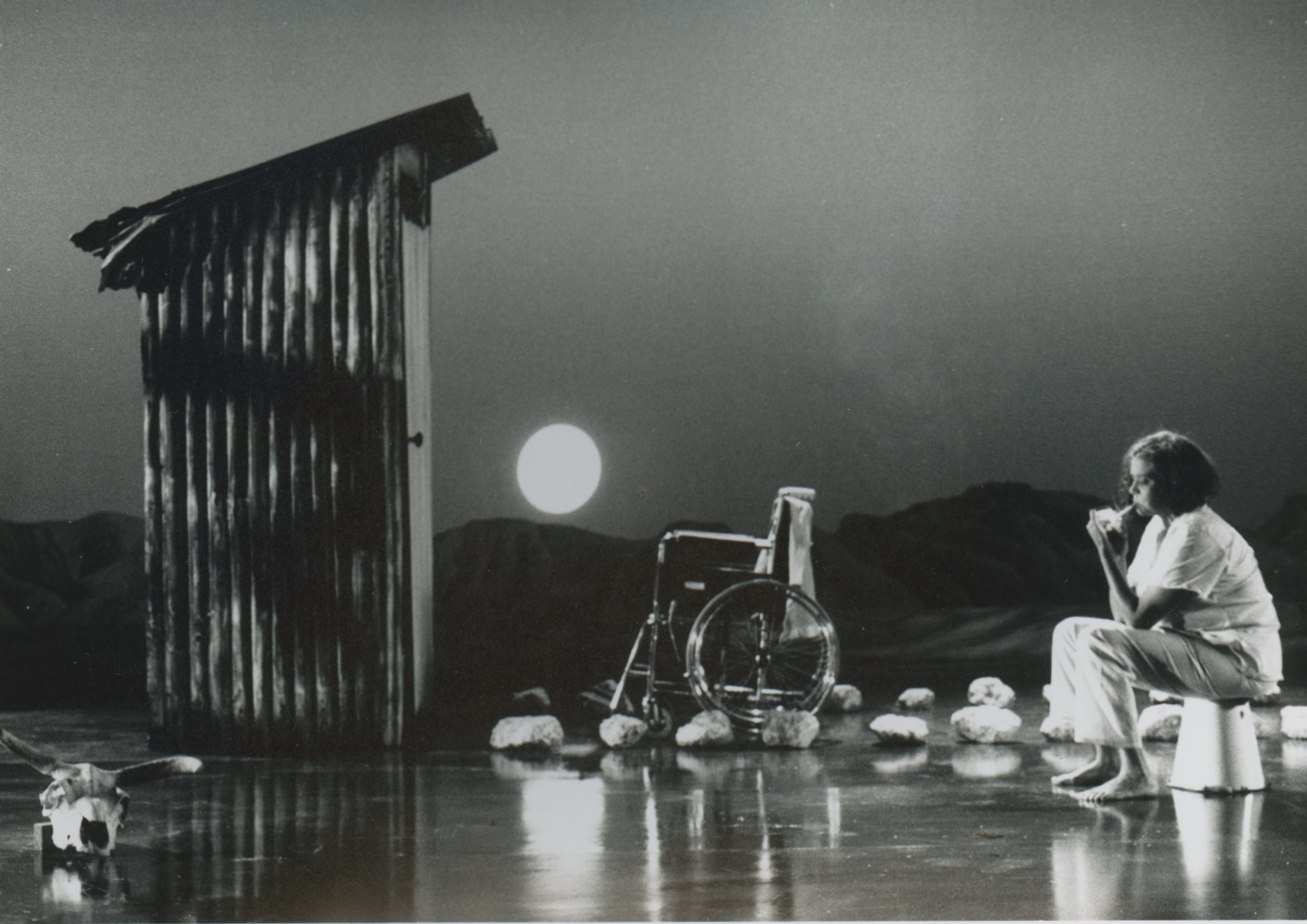

In Moffatt’s hands, working with art director, Stephen Curtis, the personal tragedy is expressed with visual metaphors of extraordinary power. The story is staged entirely in a studio: the distant hills and the red desert are defiantly and gloriously artificial, studied and constructed. Even memories of a rocky headland with waves crashing below, are staged indoors using blatantly artificial rear-projection. It’s a bold and brilliant visual concept, which Moffatt and Curtis went on to develop in her first and only feature film, BEDEVIL (1993), also available from Ronin Films.

The soundtrack too is equally bold, a non-naturalistic composite of animal shrieks and heightened “natural” sounds deriving from the action on-screen, juxtaposed with Jimmy Little singing “Royal Telephone”.

The power of the film is that through the creation of its own hermetic world, it expresses a wealth of emotions and meanings about Indigenous history, alienation and suffering. And laced through it all, enriching every frame, is Moffatt’s awareness of cinema history, beginning with a quotation from PICNIC (1955), to JEDDA and beyond. From this history, Moffatt draws a unique personal vocabulary with which she cuts deep into the crisis of Indigenous identity.

‘Moffatt draws together the elements of autobiographical material with a razor-sharp insight into issues of contemporary history with a vibrant sense of the cinematic.’ – Anne Rutherford, Artlink.

‘A breathtaking, visual film . . . It attacks and disturbs with its blunt political advocacy and touches emotionally in its gentler moments on faltering human relationships. It is proof of a new Australian filmmaking sensibility at work.’ – Scott Murray, Cinema Papers.

- The Pacific Film and Television Commission Pty Ltd, c/ Brisbane International Film Festival (2006)

- International Film Festival Rotterdam(2003)

- Creteil Film Des Femmes Festival(1999)

- Australians for Native Title and Reconciliation (1998)

- Fajr International Film Festival 1997)

- Valladolid International Film Festival(1996)

- Strictly Oz – A History of Australian Film – LACMA (1996)

- Korean Motion Picture Promotion Corp (1996)

- Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival(1995)

- Strictly Oz – A History of Australian Film (1995)

- Centenary of Australian Cinema- Retrospective of Australian Films (1995)

- Aurora Australis: New Independent Film from Australia (1995)

- International Short Film/Video Festival – Antalya (1995)

- Semana De Cine Experimental de Madrid (1994)

- Cornerhouse (1993)

- Aboriginality – Berlin (1993)

- Verona Film Festival (1992)

- Australian Film Series – The Asia Society (1992)

- Tampere International Short Film Festival(1991)

- Seattle International Film Festival (1991)

- Anteneo Feminista De Madrid (1991)

- La Mondiale De Films Et Videos De Femmes (1991)

- Hong Kong International Film Festival (1991)

- Festival\De Cinema De Douarnenez (1991)

- De Cine Y Video Realizado Por Mujeres (1991)

- Creteil Film Des Femmes Festival (1991)

- Clermont-Ferrand International Short Film Festival (1991)

- Centre Georges Pompidou, Australian – Pompidou Event (1991)

- Wellington Film Festival (1990)

- Vancouver International Film Festival (1990)

- Toronto International Film Festival(1990)

- Sydney Film Festival(1990)

- Seattle Women’s Film Festival (1990)

- Festival International Du Film D’Amiens (1990)

- New York Film Festival (1990)

- Festival International De Films Et Videos (1990)

- Melbourne International Film Festival(1990)

- London Film Festival(1990)

- Los Angeles Int Film Exposition – Filmex (1990)

- Hof International Film Festival(1990)

- Hawaii International Film Festival (1990)

- Frames Film Festival (1990)

- Edinburgh International Film Festival(1990)

- Festival Internazionale Cinema Giovani (1990)

- Cannes Film Festival(1990)

- Festival International Du Film D’Amiens (1985)